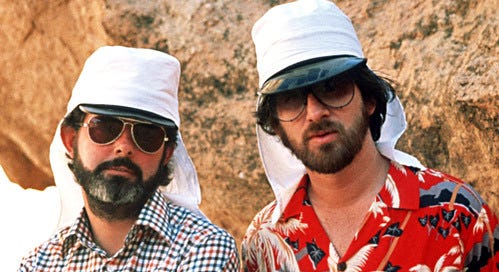

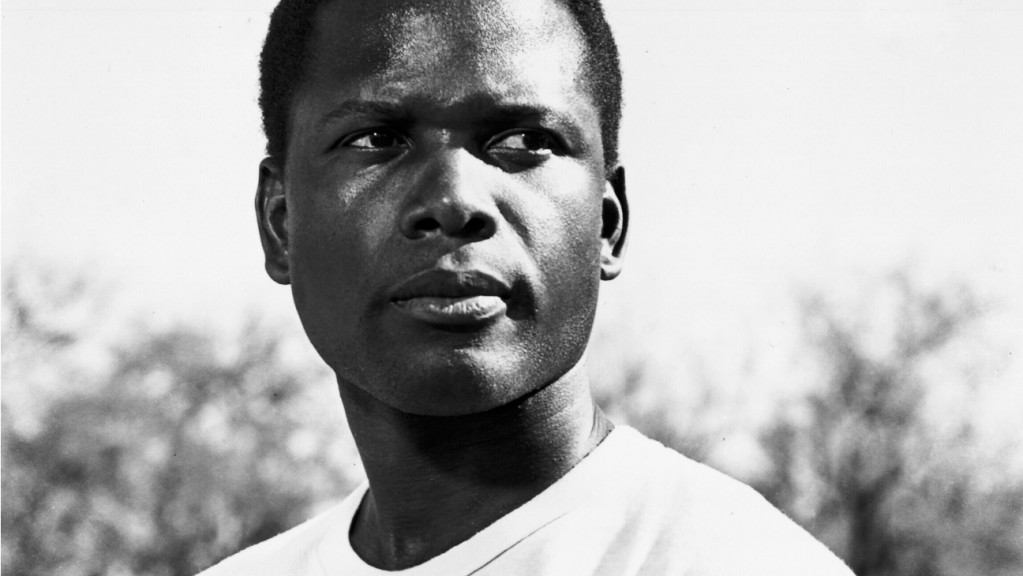

Lucas and Spielberg Sitting on a Beach

Cinema as theme parks and making movies that change lives.

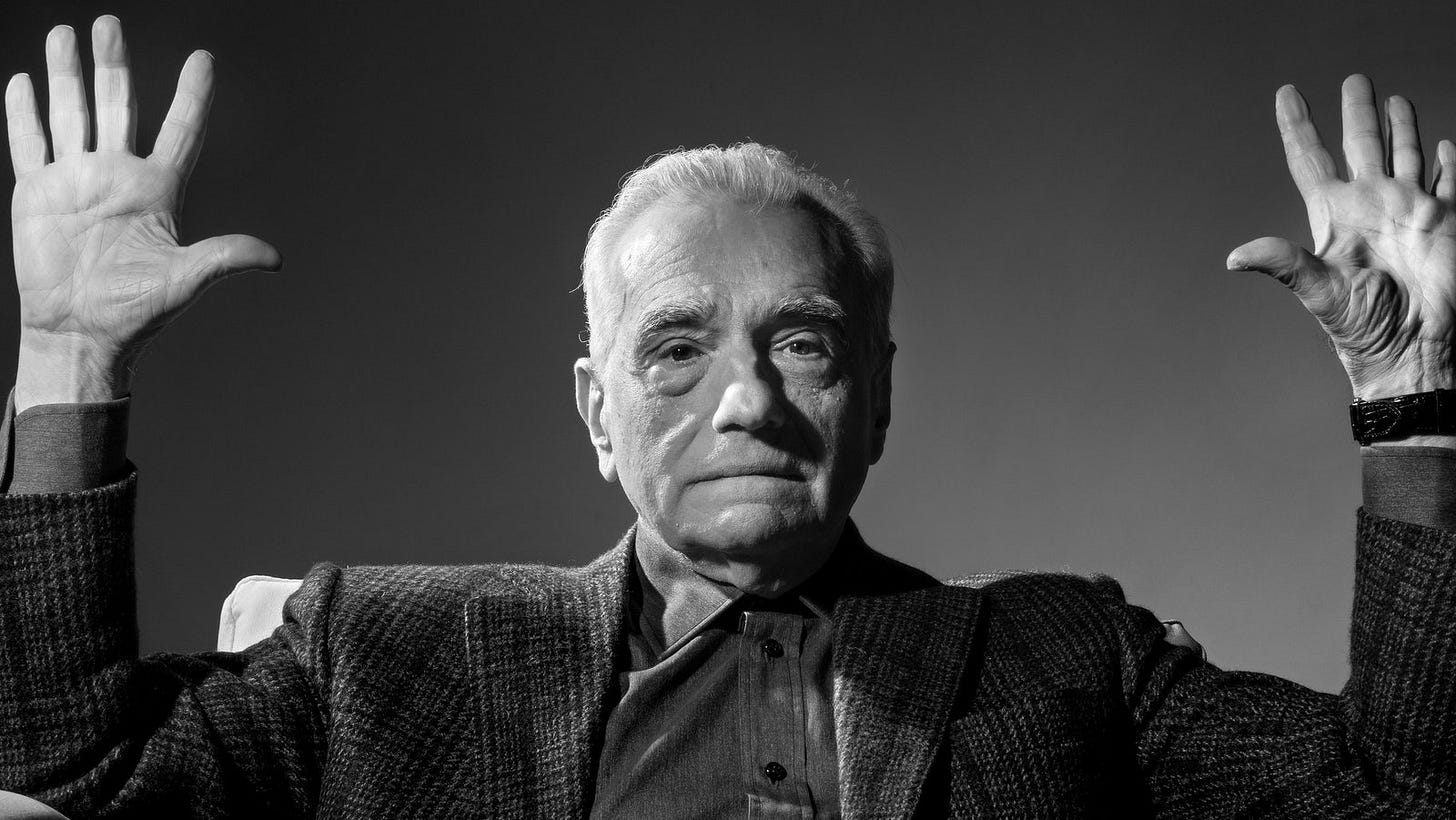

Quoted in the New York Times in 2019, director Martin Scorsese gained fame by saying, “Marvel Movies aren’t cinema.” The director of such movies as Taxi Driver and Goodfellas said, “Cinema is an art form that brings you the unexpected. In superhero movies, nothing is at risk,” he said. [1]

In The Guardian, in the same year, he said, “Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.” [2] According to the newspaper, the head of Marvel, Kevin Feige, responded to the criticism by saying, “Maybe it’s easy to dismiss VFX or flying people or spaceships or billion dollar grosses [but, he notes] Alfred Hitchock never won best director, so...it doesn’t mean everything.” He said, “I would much rather be in a room full of engaged fans.”

They are arguing about the main principle or intent behind the film’s production. One filmmaker prioritizes conveying emotional and psychological human experiences while the other strings one showstopping cinema trickery after another with a thin storyline.

I think it’s funny that this so-called “Marvel Movie” might have originated somewhere on a beach in Hawaii in the late 1970s.

True story: George Lucas and Steven Spielberg ran into each other at the Mauna Kea Beach Hotel while trying to escape the commotion from their recent successes, Star Wars (1977) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). According to the famous story, they both sat on the beach and talked while building a sand castle. Lucas and Spielberg sitting on a beach, both in their 30s at the height of their careers, were naturally talking about their following projects. From what I remember of the story, Lucas asked Spielberg what kind of movie he wanted to see. They spoke of their childhood love of old adventure serials from the 1930s and 40s, from which Star Wars came.

Spielberg said he secretly wanted to direct a James Bond film. Lucas told him about his concept for an adventure film with an Indiana Smith character. Spielberg loves the idea and calls it “a James Bond film without the hardware” but tells Lucas the last name ‘Smith’ does not sound right. Lucas replies, “OK.” (two or three beats) “What about ‘Jones’?” [3]

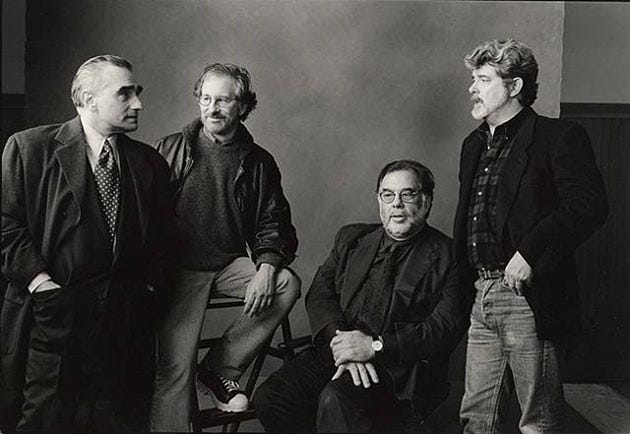

In the Introduction to an Attractive Concept, [4] Wanda Strauven wrote “As a reloaded form of cinema of attractions…recent spectacle cinema has reaffirmed its roots in stimulus and carnival rides, in what might be called the Spielberg-Lucas-Coppola cinema of effects,” (20) naming three filmmakers that ushered the blockbuster era.

According to Paul Risker in his publication Little White Lies, popular lore credits the Movie Brats of the New American Cinema as the fathers of the blockbuster film. “It has become an accepted history, despite cinema having pursued high budget and lavish spectacles long before that,” he said. [5]

However, Risker notes something different with today’s iterations. “While far from perfect, the technological limitations of the 70s and 80s imbued world-building with a specific improvised hands-on aesthetic, a world away from today’s use of computer-generated imagery and green and blue screens, which purport to increase immersion but, in reality, feel more artificial. Once, films mimicked our physical play – now, technology has allowed them to appear as dreams, almost without limitation. From Star Wars and Spielberg’s Jurassic Park to Marvel and DC superhero films, the sole focus is no longer on creative storytelling and the cinematic experience but on diversifying revenue,” he said.

According to philosopher Emmanuel Kant, “the judgement of taste is not an intellectual judgement and so not logical, but is aesthetic—which means that is one whose determining ground cannot be other than subjective” (48). “Art and criticism cooperate,” says A.O. Scott, [6] “through a kind of symbiosis that often seems to marginalize—or do away with the need for—an audience of nonprofessional, unspecialized, agendaless spectators” (61).

“The motives that bring us…to the box office window…are often casual, even banal…[but] the transformative, galvanic result of the experience was not…willed or anticipated,” says Scott, “And yet,” he continues, “somehow it happens: your everyday perception is disrupted by the sense of a presence that is hard to describe but impossible to deny” (65). Scott says this is how art speaks to us: "this challenge reverberates through the exhibition halls. It changed my life.”

Scott needs to provide examples. He reflects that it could be a figure of speech and “a hyperbolic way of acknowledging the momentarily disruptive impact of art on the equilibrium of everyday consciousness” (66). He admits that the “nature and the mechanism of the transformation—how did your life change? What was the difference before and after?—rarely receive much analysis” (66).

I learn from the actions of the people on screen in a similar way that I do in real life. For example, I learned how to make French toast from Dustin Hoffman in a scene from Kramer vs. Kramer (1979). I learn from convincing displays of information. Friends of mine turned vegetarian after seeing the film Forks Over Knives (2011), a documentary examining the reversal of degenerative diseases by rejecting our “present menu of animal-based and processed foods.” [7]

“Tears, of course,” says Scott, are a traditional measure of aesthetic response, palpable evidence that a work of art has reached beyond the shell of its existence or the clouded bubble of its creator’s intentions and made an impact in the world” (62).

I have heard countless times, as a way of complimenting me on a film I had made, the words, “You even made me cry!” I remember crying at “spectacles of sublimity,” like when I saw Van Gogh’s Crows Over the Wheat Field in a museum in Amsterdam or when I saw that shot of Christian Bale in Empire of the Sun (1987) of him walking through a field while boxes parachute down around him. (This memory is twice cherished since I recall Mr. Wayne Sargent, my high school teacher at the time, happened to be coincidentally sitting next to me at the movie theatre. When he saw my tears, he blurted “I love you” involuntarily in the dark.)

For myself, seeing Jaws (1975) as a child had a profound and lasting effect on me about the power of cinema. As I remember this story after many tellings, I have discovered a new metaphor: as a boy, I approached the screen (like the sun) as my mother urged, but then I got too close and “got burned,” so I ran back to mommy. After the humiliation of being heard screaming by the entire movie theatre, I may have reacted like any aesthete, as Scott suggests, “I want to do that. How did he do that? Maybe I could do better!” (29).

At seven years old, I did not have the means to try to “do better.” I worked through my ideas by playing with my toys and reenacting scenes from movies I had seen while playing movie soundtracks. I told myself I’d be a film director someday, but when I learned in film school that I had to play a social game to achieve this, I balked. Seeing Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil changed my life by showing me how to make a film outside the Hollywood gates with my resources. My life changed because, starting then, I made different choices and chose to walk previously unseen paths.

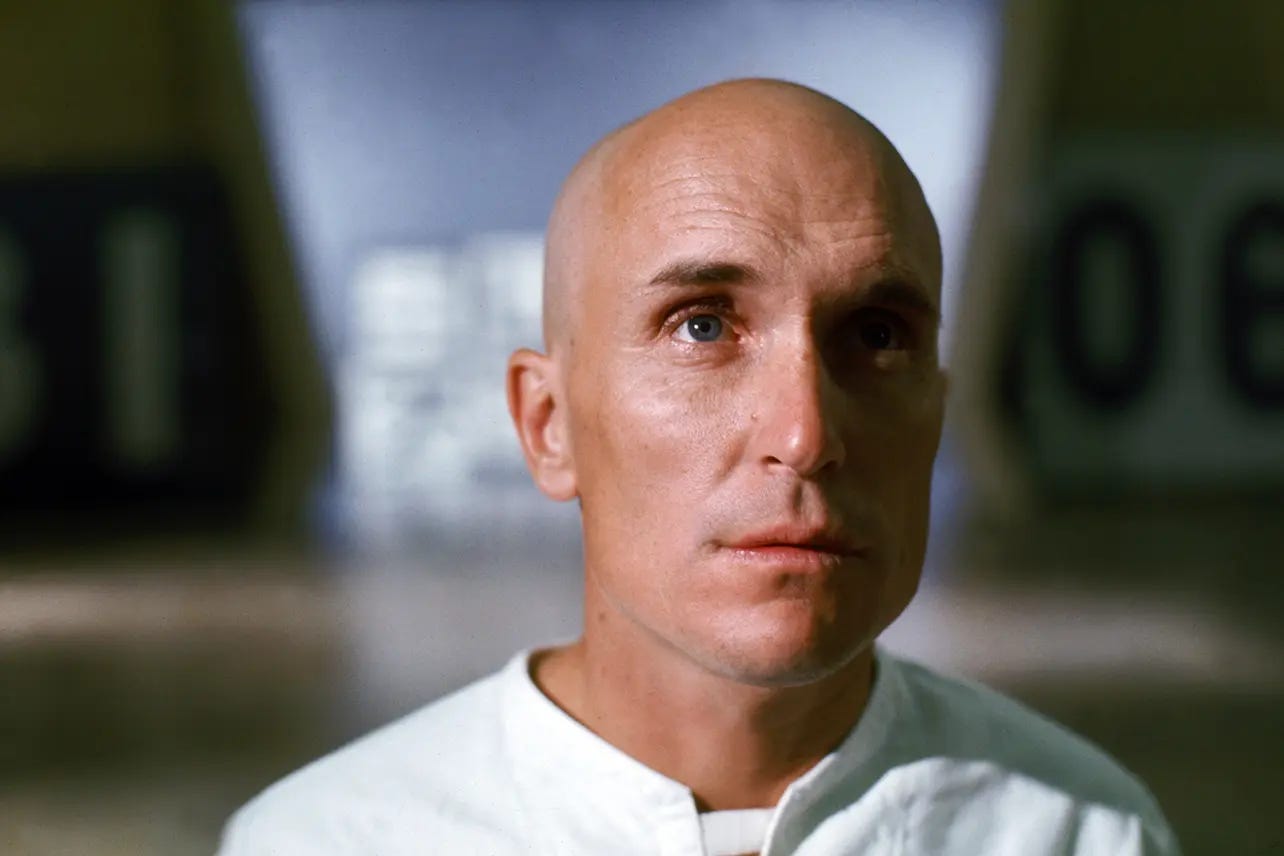

While reading Nancy Schwartz’s [8] paper, I remembered that Walter Murch edited THX 1138 (1971), and I recall a story I had read about making the film. From what I remember, director George Lucas had asked Murch to create a soundtrack to which he would supply the images. The story goes that the resulting experiment led to the making of the THX 1138. The book that Michael Ondaatje wrote [9] sits on my shelf. I flip through the book quickly, looking for the story to cite. It could be in another book that I read. Instead, I find a brief passage about the “translation of a three-dimensional object—the human face—into a two-dimensional photograph.” Murch says, “There’s a chemistry between each actor and a certain lens… I remember George Lucas being fascinated by the depth of Robert Duvall’s features, his deep-set eyes and rounded forehead. It was one of the reasons he cast Duvall…” (197 - 198).

I flipped through the book again and found this from George Lucas: “Sound was very important to us. In THX 1138, we decided to create a primarily sound effects-based soundtrack—the music would operate like sound effects, and the sound effects would operate like music” (19). Yet, I find the quote intriguing: “In school, I was very much an anti-story, anti-character kind of guy. I was of the San Francisco avant-garde film school and cinéma verité, that sort of thing” (18). The quote, I think, supports my theory of Star Wars and the conceit of starting the film with the words “Episode Four” as one of the most avant-garde gestures in Hollywood blockbuster history.

I have been thinking about the conscientious reversal of the genre of “film noir” to its opposite, “film blanc.” As I’ve written elsewhere [10], “What if instead of cynicism, there was hope? Instead of showing situations where humans are being unkind to other humans, what if a film insists on showing kindness? Instead of showing the dark side of human nature, what if it tells the story of how we can find the light in every situation? Are we ready? Film blanc may seem overly optimistic, but couldn’t we say the same heavy-handed was about film noir?

“Visions of dystopia have overrun our current mediascape. A cursory glance at the front page of Netflix on any day gives me an idea. Human unkindness and dystopia are prominently on display. If there could be a unified concerted movement to “flatten the curve” during a pandemic, then perhaps there could be a similar movement toward hacking the Netflix algorithm that determines what gets featured on the front page. After all, new types of battles are required for new wars. Specialty channels can, of course, offer an alternative but we need a massive effort to tip the scale or at least balance it.”

Schwartz notes that “very few science-fiction films have dealt with technological utopias (with the exception of the Wells-Korda-Menzies Things to Come of 1935)” (18). In his paper, J.P. Telotte [11] outlines the problem with utopia. He starts by quoting Paul Ricoeur, who suggests ideology and utopia represent “deviant attitudes toward social reality…nostalgic escapism of utopian/dystopian narratives is useful if it helps us to interrogate the prevailing conditions of our culture.”

Ricoeur says, “Our visions of utopias—or dystopias, for that matter, produce a problematic relationship to our world because of their “eclipse of praxis” in that “such fantastic constructions, much like any culture’s dominant ideology, can easily distract us from what might be done” (45).

For Paul Virilio, “Our world is inexorably becoming ‘film.’” There is a “widespread postmodern belief that reality itself has disappeared into a variety of cultural constructs, that the real ‘exists’ only as we construct it from experience, or as it is constructed for us by the many cinematic and electronic media that permeate our world.” However, the “fully imagined and convincing diegetic world” of the imagined world “undermine the critical effect of such a vision by dislocating this distinctly imagined world from our own.”

Notes

Martin Scorsese. I Said Marvel Movies Aren’t Cinema. Let Me Explain. November 4, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/04/opinion/martin-scorsese-marvel.html

Catherine Shoard. Martin Scorsese says Marvel Movies are ‘not cinema.’ October 4, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/oct/04/mseries’sorsese-says-marvel-movies-are-not-cinema

https://stevenspielbergchronicles.tumblr.com/post/132659094171/1977-in-late-may-george-lucas-is-on-vacation-in

Meanwhile, Back at the Ranch. May 21, 1989 https://www.nytimes.com/1989/05/21/movies/meanwhile-back-at-the-ranch.html

Paul Risker. The Long, Complex Evolution of the Blockbuster. https://lwlies.com/articles/the-long-complex-evolution-of-the-blockbuster

A.O. Scott. Better Living Through Criticism. Penguin Press, 2016.

Entry on Forks Over Knives, Letterboxd, https://boxd.it/1F

Nancy Schwartz. “THX 1138 vs. METROPOLIS,” The Velvet Light Trap, spring 1972; 4, Periodicals Archive Online, page 18.

Michael Ondaatje. The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film. A Borzoi book published by Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

LA Alfonso. Review: Lillies of the Field. Letterboxd, April 18, 2020, https://boxd.it/15ZXK3

J.P. Telotte. The Problem of the Real and THX 1138.

Images

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/02/movies/martin-scorsese-irishman.html

https://www.apartfrommyart.com/apart-from-my-art/sea-steven-spielberg-george-lucas

https://nerdypopcorn.wordpress.com/2019/12/15/the-movie-brats-that-changed-hollywood-forever/

https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2018/01/a-o-scott-on-harvey-weinstein-and-the-influence-of-rotten-tomatoes.html

https://www.goldderby.com/article/2019/oscar-flashback-marriage-story-kramer-vs-kramer-oscar-predictions-news/

https://reverseshot.org/symposiums/entry/763/empire_sun

Sans Soleil (1983) Directed by Chris Marker

https://decider.com/2021/03/11/thx-1138-streaming-on-hbo-max-anniversary/

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/lilies-field-review-1963-movie-1124442/