What images have bruised me?

I want to open myself up to uncover a cinema-scape.

Lynch/Oz (2023) is a film about the influence of The Wizard of Oz on David Lynch’s work; it investigates what totems, themes, and motifs he regurgitates because they’ve become “embedded in his own cultural lexicon.” Director Alexandre O. Philippe divided the feature-length essay film into six chapters, each hosted by a different perspective on the same subject, including filmmaker John Waters. In the closing chapter, David Lowery admits that as a filmmaker, he also regurgitates. Lowery says that in directing Pete’s Dragon (2016), he was surely recapitulating Spielberg’s signature camera move each time he dollied into a closeup of an actor’s face; he says that look has “embedded” itself in his “psyche throughout the years of loving Spielberg movies.” [1]

“Putting together a list of movies that I think have a seismic effect on my work,” he says, “it’s not a long list.” He counts among them the first movies he saw in the movie theatre: Disney’s Pinocchio (1940) and Spielberg’s E.T. (1982). “Those impressions run deep and are hard to escape,” says Lowery. “They’re so hard to escape that I think the majority of us as storytellers don’t try to escape them — we just dig in deeper.” He says, “We are repeatedly making the same movie and telling the same story.” Lowery thinks David Lynch’s Lost Highway was a step towards Mulholland Drive, which led to Inland Empire and further evolved to Twin Peaks: The Return.

“Once you realize what they’re digging towards, you can appreciate [the filmmaker’s] body of work in a new light because you understand what matters to them,” Lowery says. “I love the idea of digging in deeper and hitting the boundaries within the work that we’ve created for ourselves rather than trying to expand the horizons around us. I like the comfort of knowing that there’s always further inward. The themes and images that compel us are the ones we will keep re-visiting, re-exploring, re-investigating, re-contextualizing, and re-everything because they are the things that compel us to be storytellers in the first place. We look to the past while looking into the future, which is valuable for the culture.”

Is it inspiration or copying? It’s the same thing, says anime filmmaker Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell): “All cinematic creativity is quotational. But it is different from exact copying. Quotation means you run it through your own interior, thus editing it. You change the meaning, the nuance, the arrangement, and so on. So you’ll naturally see traces of me pop up here and there. Sometimes, I wonder if originality as such even exists. How you handle the quotes and whether you’re good or bad at it matters. How do you use them, and what is your unique twist? What is your intent in quoting?” [2]

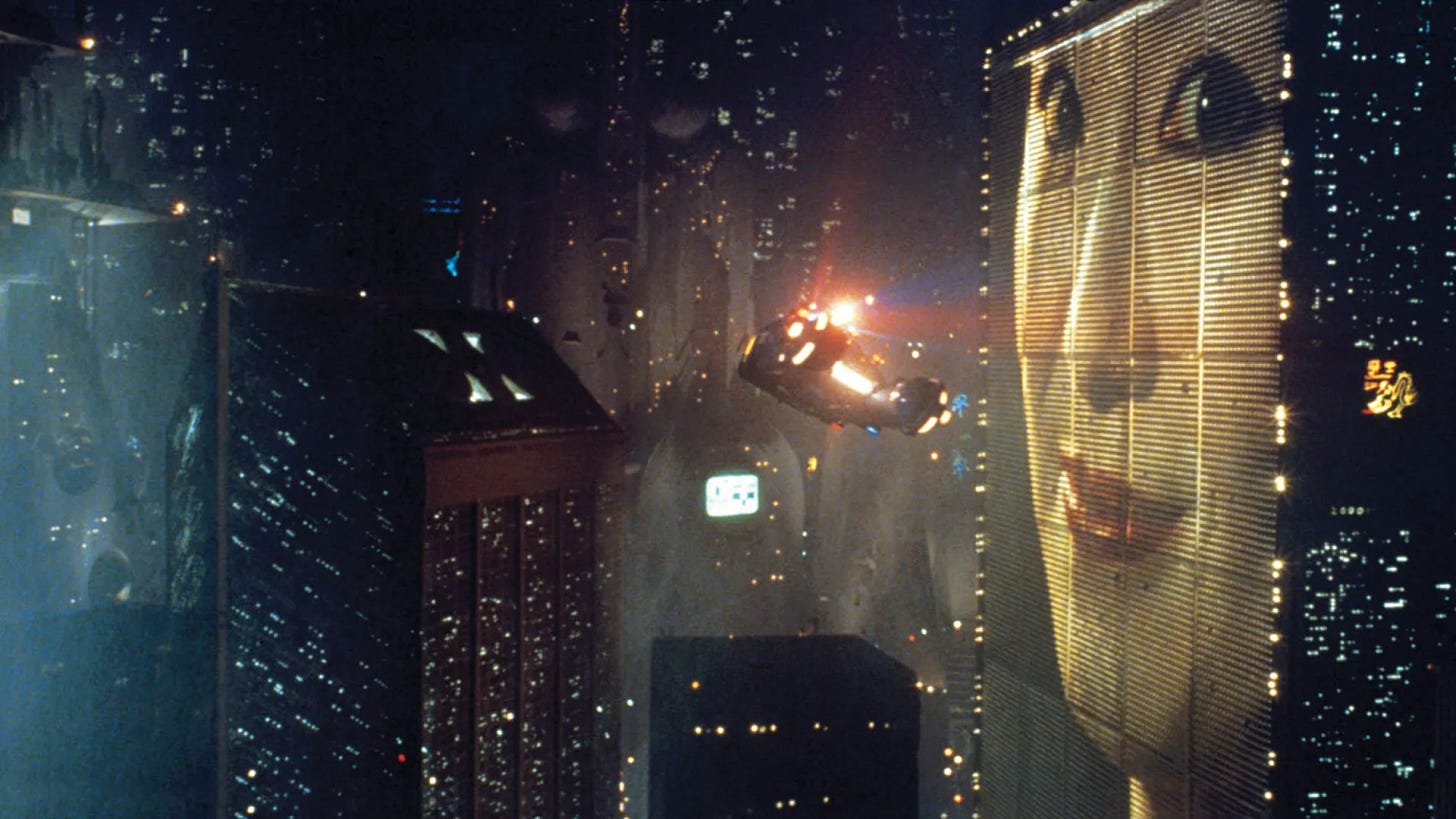

For him, Blade Runner (1982) had a profound effect. He says, “It proved what I was thinking. It was telling me it was all right to do that. You’re doing the right thing. Just do it—fearlessly.” He says, “People won’t remember the film’s plot, the actor, or the director’s name. It’s all in the details.”

In “A” is for Alice, for Amnesia, for Anamnesis: A Fairy Tale (Almost Blue) Called La Jetée, [3] writer Carol Mavor highlights Chris Marker’s words from his CD-ROM/memoir Immemory (1997): “I want to claim for the image the humility and powers of a madeleine,” he said referring to the cake that famously unlocked the door to the past for French writer Marcel Proust as recounted in his book In Search of Lost Time. Marker wanted to create an image that stirs a memory and transports the viewer like a madeleine. Like Proust, Mavor writes, “Jet-man (the hero in La Jetée) follows his ‘madeleine’ and connects it to Hitchcock’s Vertigo.” Marker noted the film deals with the extravagant quest to rediscover things past; that its heroine happens to be Madeleine is the kind of a fluke that connoisseurs can smile over” (65-66).

Mostly told with still photographs, La Jetée seems to be about the power of images themselves. The film begins with the line, “This is the story of a man marked by an image from his childhood.” Or we can say, “bruised” by an image from his childhood, as Mavor suggests in her paper, “that cropped image of a child’s legs in schoolboy shorts, standing at the bottom rail at the edge of the jetty shows a very faint bruise on the right leg” (76). This idea inspires me to ask myself, what images have bruised me?

Then, just now, I realize the image of the boy by the railing is me from the tale I’ve told a thousand times before. My origin story as a filmmaker began at the balcony railing of the movie theatre on that fateful day when my parents took me to see Jaws when I was much too young. The scene from the movie repeats itself in my head quickly today; decades later, I have instant recall. I screamed, “Mommy!” as I returned to my parents from the balcony. The entire theatre laughed. Back in my mom’s arms, in my silent humiliation, as A.O. Scott suggests, I might have reacted like any aesthete: “I want to do that. How did he do that? Maybe I could do better!” [4]

What about those old Filipino movies I grew up with? Are they still inaccessible on today’s internet? Can I find Darna and Dolphy on YouTube now? One of the first movie images I can recall is a shot of a man standing under a banana tree with his mouth wide open and tongue out, waiting for the dew to drop from the hanging banana heart at midnight. Do I have a cinematic “rosebud”? What’s been “embedded in my own cultural lexicon? I want to open myself up to uncover a cinema-scape.

I recall Chuck Workman’s compilation of iconic Hollywood images in his award-winning Precious Images (1986). “From Citizen Kane to Star Wars, from Some Like It Hot to E.T.,” the film’s description boasts, “the incredible short cuts of roughly a second each push the audience into a kind of trance and take them on a journey into their individual memories of great films of the 20th century.” [5] Films like this and other Oscar Awards supercuts have filled me with so much joy that I would cry.

When I look back at the foundational texts from which I learned the grammar of filmmaking, I cannot discount the importance of Sesame Street for teaching me the language of experimental cinema at an early age. It would be so much fun now to show clips in split screen comparisons with (avant-garde) well-known early experimental films like Ballet Mecanique (1924), Anemic Cinema (1926), and more.

Sesame Street is in my DNA; I’m excited to dig deeper. I wonder if rewatching the first movies I’ve ever seen, like Bambi (1942) and Jaws (1972), could yield new insights into what makes me tick. What comprises my short list of films that “have had a seismic effect”?

Seeing Lynch/Oz has affected my thoughts profoundly; it has shown me that a new kind of self-inquiry is possible — that I can visualize a wholly personal story by sampling Hollywood imagery. I’m excited about seeing this model or structure from which I can devise my version, drawing, as it were, from memory. Lynch/Oz, in Mamoru Oshii’s words, “proved what I was thinking. It was telling me it was all right to do that. You’re doing the right thing. Just do it—fearlessly.”

It will allow me to bring new scholarship to my work, show things I’ve never shown anyone before, and work with my vast archives of unpublished material. Stay tuned for MeMovie: Director’s Notebook.

Notes

Lynch/Oz (2023) Written and directed by Alexandre O. Philippe. Criterion Channel.

He says this in an ad for his masterclass, Anime and Film Directing with Mamoru Oshii, from "Session Five: A Katamari of Details," on Naro.tv.

Carol Mavor, “A” is for Alice, for Amnesia, for Anamnesis: A Fairy Tale (Almost Blue) Called La Jetée. Duke University Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822395461-003

A.O. Scott. Better Living Through Criticism. Penguin Press, 2016.

Entry for Precious Images. Letterboxd. https://letterboxd.com/film/precious-images/

Images

The Wizard of Oz (1939) Directed by Victor Fleming https://www.cbc.ca/radio/q/blog/the-wizard-of-oz-at-80-fascinating-facts-about-the-cursed-film-classic-1.5258255

Naomi Watts / Judy Garland / Mulholland Drive vs. The Wizard of Oz http://culturecatch.com/node/4201

Lynch/Oz (2023) Written and directed by Alexandre O. Philippe https://variety.com/2022/film/reviews/lynch-oz-review-alexandre-o-philippe-1235316915/

Blade Runner (1982) Directed by Ridley Scott https://variety.com/2017/film/columns/how-blade-runner-became-a-geek-metaphor-for-art-1202583468/

La Jetee (1962) Directed by Chris Marker https://www.a-rabbitsfoot.com/editorial/film/no-escape-memories-in-time-in-chris-markers-la-jetee/